| Wolfgang Hofkirchner Cognitive Sciences In the Perspective of a Unified Theory of Information In: Allen, J. K., Hall, M. L. W., Wilby, J. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Conference of ISSS (The International Society for the Systems Sciences), ISBN 09664183-2-8 (CD-ROM), 1999 CONTENTS:

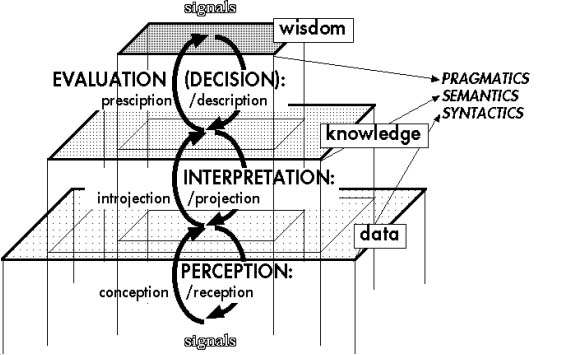

In cognitive sciences, there is a divide between a naturalistic mainstream and a culturalistic thread. The first one, known as cognitivism, comprises the symbolism and the connectionism which are based upon the assumption of the computability of cognitive processes, while the second one, the phenomenological-hermeneutic thinking, defies this very assumption and postulates, instead, features of cognition in their own right. Put together, the two approaches do not complement each other in providing an appropriate picture of the phenomenon of cognition. With regard to the role experience is thought to play in cognition, either the tradition of sensualistic and empiristic aposteriorism is continued or, in a rationalist's or in an "autist's" manner, the existence of aprioris is suggested. Concerning the relation between cognition and the objects it refers to, one has to choose either the representational stance of objectivism, or the constructivistic, solipsistic, spiritualistic or platonistic view of subjectivism. As to the intentionality of cognition, causal relationships within the cognitive realm are considered sufficient (causalism) or explanations which resort to attitudes of persons towards situations are deemed essential (intentionalism, "voluntarism"). Computationalism, on the one hand, and phenomenology and hermeneutics, on the other, are extreme positions which are one-sided and cannot be mediated as such. However, it is favorable to adopt another point of view that tries to take up those aspects which are reflected appropriately. This seems possible by applying the emergentist methodology of evolutionary systems. Thus, in human-information generating systems, perception may be looked upon as a concurrence of reception and conception resulting in data, interpretation may be conceived as an interplay of "projection" (construction) and "introjection" (adaptation) producing knowledge with meaning, and evaluation/decision may be the collaboration of descriptive and prescriptive processes leading to what, eventually, can be labeled as "wisdom," including values, ethics, morals. Keywords: computationalism; phenomenology and hermeneutics; dialectic; cognition

As in many other areas of research, cognitive sciences present a picture of heterogeneity. Specifically, there are two different fundamental schools of thought. On the one hand, there is an attempt by the mainstream to treat the human cognition process using only the disciplines of natural science, i.e. to approach it with methods of natural science, treat it as something which is as natural as anything else in nature, and on the basis of results obtained to make it an object of technological manipulation. Evidence for the naturalist approach is provided by the following:

All of these come together as the cognitive sciences. By

far the most influential model is, however, the computer metaphor of the mind, which is

represented by symbolic cognitivism and the sub-symbolic connectionism. But the computer metaphor finds its counterpart in less empirical, but transcendental, phenomenological and hermeneutical positions which correspond to Husserl, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty etc. in the same way as did the turn of psychological research towards empirical methods nourish the speculative thread because of its shortcomings. Arguments in this direction, which sometimes take account of individual, sometimes collective components of irreducible mental phenomena, are presented by some psychology doctrines, especially the psychoanalytical ones: the linguistic philosopher Searle, who criticized the linguistic turn of the analytical philosophy of the mind; the philosopher Popper, who postulates cognition without a cognitive subject; the religious brain-physiologist Eccles, Varela, who changed from neurophysiologist to neurophenomenologist, and postulated the ego-less mind; the traditional semiotic schools and to a degree biosemiotics; anthropological considerations, which bring non-historic essential characteristics for the special position of humanity into the attack; an explicitly hermeneutically named cognitive science. An anti-naturalistic attitude also makes its case. It involves using methods developed by the humanities and social sciences, seeing in the subject of human cognition a genuinely human, i.e. intellectual and cultural, phenomenon; further it strives to banish the creeping danger of incapacitation of human thought by increased mechanization and technology, whose autonomy is unavoidable. The two sides do not complement each other, but form an abrupt conflict. This is an unsatisfactory situation for science. It is the firm belief of the author that, as often happens, each side has its justification, but exaggerates this to the point where it is an obstacle to scientific research. He therefore advocates attempts to bring together the plausible parts of the two philosophies but abandon the parts that seem implausible. The core of such an integrative experiment, which orients itself towards a yet-to-be-developed theory of information science, is to be developed here from the critical appreciation of both the naturalistic and the anti-naturalistic viewpoints.

2. A Unified Theory of Information First a few words on what a satisfactory solution might look like. Given that cognition is a process, or the result of a process, that involves the activity of information-generating systems, the phenomenon of cognition may be covered by a Unified Theory of Information (UTI) which is considered feasible, by using the emerging theory of evolutionary systems as a starting point, and background theory which is looked upon as capable of unifying the differing information concepts. Philosophically speaking, the concept of information is closely connected with the concept of emergence of novelty. The appearance of new qualities in the course of the history and structure of all entities - be it phase transitions in the realm of physics or transformations surveyed by social scientists - is dealt with by a systems approach which since the seventies has been converging with evolutionary thinking, thus gradually preparing a paradigm shift in the world view which involves philosophical considerations as well. The elaboration of a theory of evolutionary systems offers a promising prospect of anchors for joining informational concerns. Insofar as self-organizing systems give rise to novelty, information generation turns out to be a property of self-organizing systems. The core of a UTI has to be formed by a concept of information which is flexible enough to perform two functions. It must relate to the most various manifestations of information, thus enabling all scientific disciplines to use a common concept; at the same time, it must be precise enough to fit the unique requirements of each individual branch of science. Thus a term is needed which combines both the general and the specific - the general as the governing laws of each form of information, the specific as those characteristics which make different types of information distinct from each other. These different types of information have to be related to, if not derived from, different types of self-organizing systems. In this way, this concept has to save research from what we have elsewhere called Capurro's trilemma (see Capurro Fleissner Hofkirchner 1997), that is, from falling back upon a reductionist way of thinking, or postulating holistic/dualistic positions which overestimate the divide between different qualities. Society, together with the individual members of which it is made up, is but another self-organizing system that constitutes that step in the overall evolution which represents the most sophisticated form of information generation we have knowledge of. Contrary to evolutionary information-generating systems on the pre-human level, the kind of self-organization which is needed to overcome the crises due to the global challenges requires actions of conscious individuals, and will not emerge from technological progress alone. Thus, individual human systems must be in a cognitive position so as to fulfil the requirements of communication and cooperation towards mastering global problems. Information generation does not mean a process which can be formalized and mapped in a mathematical function and is therefore computable. Rather, it is a process by which novelty emerges. It is bound to a certain system which is capable of organizing itself. In the course of self-organization, novel qualities come into being which characterize several levels of information. One can speak of information in the situation where the deterministic connection between cause and effect is broken up, that is, where a system's own activity comes into play, and the cause becomes the mere trigger of self-determined processes in the system, which finally result in the effect which is constituted by the reaction of the system to an event, by the response of it to a stimulus, or by the solution to a problem - in short, where the system makes a decision and a possibility is realized by an irreducible choice.

3. The pitfalls of cognitive sciences The fundamental questions of cognition theory, discussed for centuries by philosophers, was reformulated by Dennet (1988, 283) for cognition sciences as follows: "How is it possible for a physical thing - a person, an animal, a robot - to extract knowledge of the world from perception, and then exploit that knowledge in the guidance of successful action?" He thus determines the subject of the cognition process, which can be human, biological or artificial, and the stages of the process, namely perception, knowledge of the world, and guidance. For each of the three cases we can now ask how it arises and what it is built upon. It is a general problem of human cognition that perception, experience, has both a side which may be called receptive and has an affinity to the senses, and a side which may be called conceptive, and can be allocated to rational understanding. The problem with experience is how sensitive and rational cognition, perceiving and comprehending thinking are linked to each, and whether the sensitive contemplation produces the basis for the concepts. It's another general cognitive problem, how far concepts and propositions should or must be knowledge, representing an objective reality, with which they come in touch not only projectively, but also introjectively, that is, not only by conjectures, but also by means of maps. The question is whether the subjective constructions do reconstruct ideally objects, and if so, how the subjects can make sure that their conjectures do correspond with what they shall represent. There is a third problem in the guidance of action. It concerns how the depicting aspect and the instructing aspect, namely the aspect that human cognition is descriptive and the aspect that it is prescriptive, can be combined with each other. How can instructions be made from depictions , intentions from representations, when the first define knowledge as facts and objectivity, the latter as decisions for specific actions. The fundamental problems of human cognition (to which the

cognitive sciences are obliged to have a viewpoint, whether or not they want to) are as

follows: Cognitivism and connectionism, in answering the questions, orient themselves towards a model of information processing, according to which the internal processing of information, regardless of whether it is human beings (in the form of the biological organization of the family, or carried forward to a super-individual organization, which is also seen as an information-processing system), non-human organisms or computers, functions on the same principles, from the input (the reception of signals via sensory organs) to the output (the sending of messages to control the motor center). They attempt to answer the questions using the same pattern. The basic assumption is that the transitions between the different stages of information processing can be calculated and computed . Thus they try to model these transitions, i.e. all cognitive systems are modeled as embodiments of the functioning of a single information-processing system, namely the computer. This attempt to reduce the mind to a series of calculations, which appear from the functioning of the neuro-physiological substrate to be suggested, but can also be realized in architectures other than the (human) brain, requires the attempt to create a hearing for the not-yet-dead irreducible mind side, and thus a division between an "exact" scientific, calculating mind, and a transcendental mind which survives as indestructible remnants, in which the body-soul dualism is continued as a dichotomy of brain and consciousness. Depending on the subordinate range of the transcendental consciousness, the calculation will be granted either no autonomous area (expansionist variant), or one of variable size (isolationist variant).

3.1. Sensualism/empirism versus rationalism and other apriorism The first problem for cognitive science is known in cognitive sciences as, amongst other things, a frame problem. This shows itself in that, when building artificial systems that can have experiences, it is unknown how to ensure that artificial intelligence systems are capable of the generalizations typical of human cognitive systems (and it seems inexplicable how human systems can perform these things). Thus the question of the foundations of cognition is raised: what interactions should be assumed between the data coming from the sensory organs, and knowledge in general? Is there a process of generalization, so that it can be said that the concepts are based on contemplative sensations? The cognivistic and connectionistic solution being sought is part of the tradition of sensualism and empirism, in that it grasps cognition as an aposteriori, which comes after experience and must be produced from it, whereby it levels down the transition from a lower to a higher form of cognition. This leveling down happens in computationalism by the acceptance of mathematical transformability of the information in itself. According to the phenomenological-hermeneutical solution, the reverse of this process is supposed to make comprehensible all levels of cognition (rationalism), or a sealed-off area, relative to lower forms of cognition, exists (autism). These schemes and frames thus play the role of aprioris for every concrete cognitive process. In particular, three levels of cognition can be identified, on which the problems of change in quality from one form to the other can be expounded, and on which either the reduction of the differences to the lowest level, or their levitation to a higher level, or their simple ignoral, can take effect. Firstly, there is a problem of the transition at the interface of environment and system. That is to say, there is here already a process, in which an input has to cross the system boundary from outside to inside, and thus undergoes a transformation. This problem is termed "transduction." The materialistic way of thinking does not find itself confronted with a problem here, as long as nothing speaks against the stimuli having an effect like causes on the highly specialized receptor and sensory cells, thus producing effects, namely sensations, according to a pre-defined mechanism which can be treated as a mathematical function. The external stimulus transforms itself clearly into an internal sensation. Empirical findings show, however, that this is not the case, and that the sensory cells have a range of different sensibilities, and different means and patterns of reaction to stimuli. The idealistic, mental view does not give the senses an excellent position. Either the stimulation of the senses becomes an activity of mind processes in the rationalistic program, or in the autistic program it is separated from the mind processes, as the famous example of neural connections in the visual system shows. Even if such a high level of self-reference has to be granted to the cognitive processes, that the affections of the senses appear to be no more than modulations of the cognitive processes, we are still talking about influences which are apparently sufficient to give a basis for cognitive and behavioral actions, in which the cognitive systems take account of their surroundings. Secondly, there exist inside the cognitive system problems of the transition between various lower and higher levels of the cognition process. Let us now consider the non-linguistic, pre-linguistic and sub-linguistic forms of cognition. In various psychological teachings, sensory experiences count as the simple, elementary, physical impressions which cannot be broken down into simpler units. They arise from the physical stimulation of a sense (organ), whilst the perception with consciousness, in particular the conscious reflexive observation, is seen as a more complex happening at the other end of the scale of physical content. In the one view, the complex perception is built up of the simple sensory experiences. In terms of philosophical history, the determinism which is expressed by this view of the relationship of sensing and perceiving, ranges back to Locke, Berkeley and Hume. However, the cognitivistic view of the bottom-up process gets into difficulties due to several phenomena in perception psychology. These indicate that perception cannot be carried out solely on the basis of the sensory input available to the organism. This circumstance is useful to the mentalistic view. According to this, perception is not a bottom-up process, at the end of which the products are connected to mental content; rather the incoming information is constantly fitted in to expectations, which are implemented as circumstances of the short-term/working memory. Perception is something which is determined by selective attention, presupposition, inner goals, and the context of actions. Where this pre-knowledge comes from, however, if not via the senses from the interaction of the cognitive system with the environment, is not clear. Let us now consider a further area between the area of linguistic forms and that of non-linguistic, pre-linguistic and sub-linguistic forms of cognition. Since the end of the 1960's, the question has been considered in the cognitive sciences whether there are, in addition to the propositional format (in which conceptions appear to be present, that is mental representations which are independent of simultaneous stimulation of the senses), other formats, illustrating visual conceptions or non-linguistic acoustic and haptic conceptions. In the cognitivistic and connectionist model of predictability, which demands unambiguous formulation for mathematical functions, the visual conception format must be unambiguously convertible into the linguistic format. Actually, the assumption of an analogous representation system means that - contrary to a digital one - it is not allowed to reach a definite result but that operations have exclusively approximative nature which entails that results lie within a room of tolerance only. Implicit knowledge may be defined as follows. It is knowledge of which one person is not aware, and on which he/she therefore cannot give information, but which may be assumed to be present in him/her (on the basis that he or she could fulfil a specific task requiring this knowledge). From the example of implicit knowledge, the opposite can be seen, namely that not all experiences translate into language, which is the line proposed by the rationalistic model. The origin of language remains unknown. Finally, let us turn to the linguistic forms of cognition. This concerns the relationship of concepts and propositions which are close to experience and terms which are far removed from it. The empiristical position here claims that observation terms and statements are something to which terms and statements can logically be brought back to, namely all terms must be verifiable by observation terms, and all statements by observation statements. At the latest since Popper's dismissal of the logical empirism of the Vienna circle, documented in his Logic of Research 1934/1935, it has been clear that induction cannot be justified by formal logic and is not an inescapable conclusion. Popper's searchlight theory, which allows experiences to be had and observations to be made only in the light of pre-suppositions which have already been made, prepared the way for the currently widespread view that observation terms and phrases are so dependent on terms and phrases which are not open to observation, that we can no longer speak of an independent existence of observation terms and statements. According to this, every observation would be a general supposition. Against this termination of the rationalist central theme there is the circumstance that e.g. basic propositions cannot be derived from universal propositions alone, but only in connection with other basic propositions. The unruliness of the basic propositions against their subordinacy to universal propositions has a major influence on isolationism. Thirdly, there is within cognitive systems a problem of the transition from objective cognition to subjective cognition, i.e. from physical events to psychological events. The sensory perception, feelings, linguistic conceptions, abstract terms and general statements are all cognition which is processed by the cognitive system as information with various levels of quality. They are together and individually also impressions which are experienced by the cognitive system as a subject. Cognitivism and connectionism have no other choice than to deny the existence of these phenomenal characteristics of impressions, as long as they cannot explain them by the characteristics of information-processing systems. From the mentalistic position, either all cognition is made into impressions, or an unbreachable barrier is placed between them at some point. The phenomenal characteristic of cognition in the area of experience is for its part introduced as something transcendental and irreducible. In summary, the problem of the foundations of cognition is not solved by naturalistic or anti-naturalistic premises. On the one hand, the basic condition of computationalism, that information processing in cognitive systems begins with the sensual experience and is then continued sequentially or parallel and brings results using algorithmic processes, hinders the task of explaining how the system processes its high-level cognition. They cannot be obtained by algorithmic operations on sensory stimuli. The mentalistic insistence on their precedence over all experience throws no light on the question of the production of new cognition by the cognitive system, where it observes that the old ones are insufficient to reach an adequate behavior. The constant reference to a successively more advanced apriori in cognition is after all an invitation to irrationalism.

3.2. Representationalism versus constructivism and other subjectivism The second fundamental problem of human cognition is addressed by e.g. the problems of symbol grounding and the Chinese room. In the first case it is questionable how the symbolic entities came to be applied to their objects. How is the relationship to the environment made, how is the meaning constituted? In the second case, the problem is how the semantic structures can be imposed on the syntactical structures. Again we are talking about the allocation of meaning. Who applies what meaning to which objects, and why? Is there a process of making things true, so that the random nature of allocation of meaning is removed, and symbols acquire a reality content, enabling a progression from symbols with lower reality content to ones with higher reality content? If transduction and transformations in experience are represented in both cognivistic and connectionist programs as a form of one-way street, in which correct calculation steps lead clearly from one section to another, then the symbols being operated on possess objective meaning, which thus does not need to be assigned by the subject. Considering the sensualistic-empiristic principle that contact with the environment occurs via (sensual) experience, it must then be claimed that it is the objects of the environment that inhere meaning. This meaning cannot be ambiguous. In the model of information transfer, which serves here as a foundation, the recipients, that is the cognitive systems receiving information, shall be forced to adopt the same state as has the information transmitting cognitive system which makes obvious its state by just this transmission. Informing the recipient is equivalent to bringing it into line with the transmitter, i.e. imposing the transmitter's view on it. The information in the receiving system is thus a representation of the transmitting physical reality. As representations the symbols mean in this context the objects to which they refer; thus regarding the problem of assigning meaning to the symbols, symbols are already anchored in the objects, and regarding the problem of the Chinese room, the semantics is delivered along with the syntax of the symbols. This attempted solution cannot however guarantee genuine closeness of the representation to reality or coming closer to this. Firstly, neurosciences provide no evidence for isomorphic or homomorphic representations. Secondly, in semiotics and linguistics it is assumed that syntax and semantics are indeed closely combined with each other, but not identical, and so cannot replace each other. Thirdly, certain linguistic expressions cannot be verified, i.e. the correspondence between them and what they express may exceed the bounds of what can be observed to be true. The common features of the various mentalistic advances in the problems of symbol-anchoring and the Chinese room are that the assignment of meaning is seen as an intellectual act of the subject, which for its part happens without condition and is not controlled by anything else. The differences lie in whether the intellectual act is considered to be something which collects material processes and results (constructivism and spiritualism) or distances itself from these things (solipsism and Platonism), and also in whether the subject is seen as an individual (constructivism and solipsism) or a collective (spiritualism and Platonism). The symbols are not anchored in reality, and the objects of reality have no meaning in themselves, is the answer of mentalism. What the mental performance brings, at least that on a higher level, is not representations, but constructions of individual worlds and realities, in which individual participants (or leading members of the group) live for themselves, and contain their own meanings. It must be noted that there is no explanation for the way cognitive systems learn, i.e. have experiences which cause cognition to be improved, as long as any theories cannot be disproved by reality. Every failure, every collision would be an already-constructed experience, dependent on the context of meaning of the system, and so in turn is nothing more than a suspicion. Cognition remains within itself, the systems remain with their perception alone, without any possibility of concrete interaction with hard reality. It cannot be explained how the systems are able to cope with their environment.

3.3. Causalism versus intentionalism and other normativism The third basic problem of cognitive science is also known as Brentano's problem. It concerns whether, in the explanation of cognitive acts, intention and attitude of the subject may or must appear, or whether purely causal explanations are sufficient. It considers the connection between being and obligation: how is the insight of the cognitive system into its place in the environment, connected to its intention to maintain or change the situation? Does human cognition have its purpose in serving as the basis for decisions on acting in special situations? Is there a process of valuation, whereby we can say that instructions for action with a demanding character arise from different cognitive entities than do those which have a stative character? If the circle of cognitive processes from input via throughput to output of the system is neurobiologically sealed, and the order of the various process steps representing a series of calculations, working on the principles of technical information-processing (logical-mathematical links), can be reconstructed, then the metamorphosis of the cognition is causally completed. This means there are cause-and-effect connections which completely cover the need to explain the transformation of cognition, and reach as far as the initiation and control of actions or of the behavior of the cognitive system. Intentions, plans, goals, the will, all are instances of consciousness, of which everyday psychology attributes the production of deeds, and may be traced back along causal chains without a single non-material link. Causalism gets into difficulties here, in that it has to defend a deterministic picture of the world, which has no place for the free will of human beings. Additionally, it cannot explain how expression, subjective experience of an impulse of will, can exist, when such a thing cannot objectively exist. Mentalism demands from the participating perspectives the appointment of humans to all their inalienable rights. It sees either all cognitive actions from the outset in the subjective light of belief, hope, love etc. or removed from free will, detached from all conditions of material nature; the first, expanding form is termed intentionalism, the second, which urges isolation, is known as voluntarism. Both directions, the intentionalist and the voluntarist, fail in the task of connecting human acts (which have to be treated with terms of consciousness, and color cognition by the subjective valuation) and the processes of the organism, which in the technical/natural-science oriented terminology is supposed to provide the basis representative descriptions of its environment. Not only are intentional expressions not derivable from expressions that are their content, it is equally impossible to derive such expressions from intentional expressions. From the truth in the sentence, "Paul believes in men from Mars" we learn nothing about whether the sentence, "There are men from Mars" is true or false. "Should" clauses cannot be made into "Be" clauses. Thus the is-ought problem addressed in Brentanos problem remains open.

4. A multi-stage model of cognition In the treatment of the basic problems of cognition (its foundations, improvements, its purpose) it can be seen that naturalism and anti-naturalism either level out and lead back the existing qualitative differences within cognition to one side or the other, or they make them absolute and apparently independent of each other. They offer no solutions, no mediation of (1) sensing and reflecting, (2) mapping and constructing, or (3) representing and intending. In order to achieve such mediation, another model is needed. Cognition is not a process of transferal, receiving, processing, storage and down-loading of information on the way from the outer world to the inner, or the result of such a process, or the product of production of arbitrariness of a largely self-dependent, informationally closed subject. It is all of these. It is accepted that cognition is related to outside worlds and is the action of a subject. Cognition is the putting itself of a subject into a relationship, or the resultant relatedness of a subject to something other than itself, in informational terms. It is the happening of events or the adjustment of states in a subject which arise from its own activity and are related by the subject to events or states of the outside world. What is denied, however, is that cognition touches operations which make information appear to be fully convertible within itself, or that it consists entirely of any sort of creations, which are incompatible with each other. The informational happening which lies at the base of cognition should be considered to be layered. The informational occurrences and conditions do not form either in the transition from the outer world to the inner, or in the inner world itself, a sequence of varying expressions, either similar to each other or different. Rather they form a well-ordered construction in which levels of higher and lower quality can be distinguished. Higher levels depend on the existence of lower ones, but cannot be reduced to these alone or explained entirely in terms of them. The questions of experience, representation and motivation

may be regarded as problems that are situated on ordered levels, on which, measured by

specific criteria, transformation of information from lower to higher levels is taking

place (see fig. 1). Fig. 1: Layers and phases in human cognition The lowest level of information generation is that of perception, on which signals are made methodically into impressions, which may be called data. The middle level is that of the interpretation of real situations, on which meaning is given to the data, resulting in the formation of knowledge. Finally comes the uppermost layer, evaluation, in which sense is made of the knowledge. This involves knowledge being related to goals, which the cognitive system practically follows, and the obtaining of wisdom. On the lowest level a criterion of grasping the - in the eyes of a system - essential aspects of its surrounding marks the transition from intuition to reflection, on the middle level another - that of correspondence between the ideal reproduction and the reproduced facts - shows the transition from constructions to maps, and the criterion on the highest level, which refers to the validity of goals, indicates the change from representations to intentions. That is, process and products of human cognition are grasped as a unit by moments which oppose each other, rely on each other and form such an asymmetrical relationship to each other that the one has priority over the other. These moments are, on the level of interpretation, projecting and introjecting, and, on the level of evaluation, describing and prescribing. The respective latter moment is considered to be the dominant one, which provides the criterion for the quality of the relevant cognitive part-process and part result. A human cognitive system appropriately builds various layers of subsystems within each other, in which structures on higher levels originate from some agency on lower levels (hence the upward arrows in the figure), but, once established, are fed back in a way of downward causation to this very agency in enabling as well as constraining further agency (hence the downward arrows in the figure).

4.1. Perception as unity of reception and conception The necessity of keeping separate two opposing moments on the one hand, and the necessity of bringing them together on the other, so that they complement each other to form a unified process of experience and perception, has been stressed in the history of philosophy and science. A possible dialectic solution differs from the computationalist or mentalist variants in that it determines the relevant moments to be opposing, both necessary, and one higher than the other. The result is that the higher moment cannot be reduced to the lower, but nonetheless remains bound up with it and cannot exist without it. The lower moment is named reception, the higher conception, the union of the two perception, whereby it must be remembered that the terms have to describe both a process and its result. Receiving and conceiving are the moments of cognition methods, which swing backwards and forwards between the levels of experience. Receiving applies itself to the uptake of signals, which come from the perceivable environment of the cognitive system; conceiving is devoted to the registration and bringing together of the signals to a "view" of some aspects of the environment. The uptake of the signals starts with a particular state of experience of the cognitive system, which appears in the form of a cognition product and may be termed [concrete]n : a presentation of the cognitive environment, in which the diversity appears to the system as a certain indiscriminate nature. The signals taken up in this state, from this viewpoint of the system, identify and isolate particular aspects of the environment and bring forth a product which may be called [abstract]n : a presentation of individuals which are filtered out by the sensory activity of the system (the sensory experience is in this sense abstract, in that it only highlights isolated sides in their isolation). The bringing together of the two sides, analytically separated in the abstraction, to form a synthetic combined impression (which may impart a new view of the environment), is the product of an opposing movement of the cognition process, which is henceforth shown as [concrete]n+1: a presentation of the environment in which its diversity appears to the system in a new unity, under the condition of the new differentiation (the "rational" comprehending is concrete, in the sense that it integrates the various sides to a whole). Reception and conception are not methods which transform concrete and abstract via calculation into one another; rather they complete jumps, which are the only possible means for changing from one quality to the next. The total movement of perception becomes an unceasing oscillation between reception and conception in which the degree to which the experience is concrete, the degree of integration of ever-more differentiated impressions, and the degree to which the ever more diversely experienced environment is grasped, increase in (small) jumps. The phenomenal character of perception, which is dear to mentalism, may be understood as a manifestation of the respective total impression, which adjusts itself when the view acquires a new quality, which the previous impressions did not have. The frame of the frame-problem can then be interpreted as the respective concrete concept, on whose background the system has its experiences. What causes artificial cognitive systems to fail is that they do not have the inductive, intuitive, creative methods at their disposal, which allow natural cognitive systems to progress from concretion to concretion, thus altering their frames. The pre-knowledge which is built into natural cognitive systems, can be understood as the product of accumulated experience.

4.2. Interpretation as unity of projection and introjection The problem of representation often presents itself in cognition as a dichotomy between conceptions, namely those which work on an instruction of the cognitive system by the environment, and those that give priority to the construction of cognition by the system. Thus, in the sense of a unified conception, the moment of correspondence of representation with the environment of the cognitive system (with the condition that it may not be fixed as if the cognition process were a set path of instruction dictated by the environment) has to be seen as the dominant moment, which gives the other moment, the production of constructs, its purpose. However, it is clear from the rejection of the ability to make all cognitive methods algorithmic, that the subordinate moment is essential, and represents the creative production of original ideas in the cognitive process. Thus the interpretation, as a process of self-relating of the cognitive system to a specific constellation of its surrounding elements, and as a result of this process, becomes an interplay of projection and introjection. Here the introjection plays the crucial factor for the quality of the results of cognition to correspond with the representandum more or less, that is, to be constructs that reconstruct more or less appropriately the features of the representandum, that is, to reproduce them in a way that allows the cognitive system to behave without being frustrated by reality. This quality of design and portrayal is called truth. The process of approaching the truth and the cumulation of cognition can be considered like this: it begins with a certain state of interpretation, which for the cognitive system represents the adequate basis for decision for its previous acts in the environment. This may be called [absolute truth]n. This model projects the system onto reality, in that it applies its knowledge to the data. In the event of incompatibility between knowledge and data, when either knowledge or data have changed, knowledge has to reinterpret the data, in order that they are compatible with the knowledge (a top-down adjustment from the level of presentation to the level of experience). Alternatively, knowledge may be converted in such a way that it interprets the data differently, again resulting in conformity between the two (a bottom-up adjustment from the level of experience to the level of presentation). In either case the interpretation changes, namely, if the knowledge is fixed, a new interpretation of the data is carried out, and if the data is fixed, the knowledge has to be interpreted differently. In both cases, the character of the state of interpretation, of being constructed by a specific system, of being hypothetical and relative, becomes apparent. This state may be called [relative truth]n. In that the cognitive system now puts it to the test and the new interpretation proves itself, as long as successful actions can be made which are based on it, it can be said that the system has introjected reality by the new model, that new areas of reality have been brought into the model and presented. This state may be described as [absolute truth]n+1. Here too there are opposing processes, projection and introjection, which become the motor of the endless movement of cognition, which is raised to ever-increasing levels of truth. The problems of symbol grounding and the Chinese room may be set out as follows. The symbols do not in themselves possess any form of anchoring, which the cognitivistic view takes for granted. It is rather the system that tries to anchor the symbols in the (outer) world, as underlined by mentalism. However, the anchoring succeeds as soon as it becomes clear that the symbols correspond to whatever it is that they are supposed to mean. The meaning is what falls to the symbols, the cognition, when the system interprets a constellation of factors in the environment as a comprehensive situation, and makes a single view out of the many possible different views. The meaning is indeed the reference of the representation to the object, as expounded by cognitivism, but as the representation of this object it is a subjective proposal, which can only be regarded as a product of the system, the reference is only valid within the framework of the system. This is stressed in the mentalistic view.

4.3. Evaluation as unity of description and prescription In the treatment of the dichotomy of recognizing and striving, which was mentioned by Aristotle, it must be considered that recognizing is shaped by striving, just as striving is shaped by recognizing, i.e. neither is independent of the other regarding its structure and genesis. Values are created by the fact that the subject puts its knowledge into the context of its goals. This action and the accompanying result are known as evaluation, and refer to the whole process/result, in which views and intentions are woven into structural-genetic relationships. One of its moments is called description, the other prescription. Prescription is the moment, which conveys the change of presentation into the instructions for action and the creation of a higher level of quality. Details of evaluation are as follows. The description starts with a particular state of valuations, goals, instructions for action, which serve as informational motivation of the cognitive system's behavior. This state is known as [subjectivity]n. The process starts when the subject, which finds itself in a particular situation, poses the problem of changing this situation and reaching a goal situation, which from the viewpoint of the subject is better, nicer, fairer, without there being an appropriate process known for reaching this goal. The subjective becomes noticeable in that the way of seeing the problem expresses bias by selecting, from a range of different possibilities, a particular state to be created. In the descriptive phase an operation should be researched which should lead to a goal. This is to say, an operation for which it is true that a connection exists, which is independent of the subject and its requirements and interests, between the starting state and the goal state, and that the carrying out of the operation causes the change from the former to the latter state. Knowledge is here objective in that the possible solution to the problem formulates facts, namely that the starting state and the operation represent a necessary or sufficient condition for the goal state, on the grounds of the objective composition of the contexts. The goal state is a state of instructions which accordingly is called [objectivity]n. In the prescriptive phase, the decision is made on the carrying out of the operation, which means making a choice as to which of the possible solutions should be selected. This is therefore a state of instruction of the subject, we may call it [subjectivity]n+1, which can be differentiated from state [subjectivity]n by knowledge about the purposeful operation, and from state [objectivity]n by the demand for action. This too is a figure that returns again and again, in which cognition starts with the subjective in the posing of the problem, advances in the description to the objective of possible solutions, whereby the subjective is sublated by the objective, and reaches the subjective of the actual solution to the problem via the prescription, where the subjective sublates the objective. Thus the description exists as subordinate moment of its unity with the prescription, and the cognition process cumulates in "wisdom," seen as the foundation of correct decisions that lead the creation of situations which are seen by the subject as better, pleasant nicer and just fairer. Here too it is the unified character of the valuation that as a new quality establishes sense, becomes an intention, and thus gives sense to the views. Thus there is intentionality of cognition. It is the sense of cognition that is oriented: It is the orientation of cognition towards the good, the pleasant and the just (but not abruptly to the true), i.e. the overall goals of the action. It is not the state of being oriented towards an object (that belongs in the context of semantics represented here, and is treated on the level of presentation and interpretation), but rather the how of the state of being oriented towards something, not the orientation itself, but rather the color of orientation, that makes the pragmatic topic of the reason for the system behavior, the demand for action, the evaluation.

Capurro, R., Fleissner, P., and Hofkirchner, W. 1997. "Is a Unified Theory of Information Feasible? A Trialogue," World Futures Vol. 49(3-4) & 50(1-4):213-234. Dennett, D. C. 1988, "When Philosophers Encounter Artificial Intelligence", in: The Artificial Intelligence Debate, (S. R. Graubard, ed.) Cambridge (MA): MIT-Press, pp. 283-295. |